In response to my last blog entry, “Bill C-36, A Better Direction For Prostitutes?” I received a letter from a gentleman who sees things differently. In fact, we’re in direct opposition. Essentially, he thinks buying sex should be allowed in Canada; I do not.

William writes: “I am a ‘john’. I buy the services of escorts, companions, prostitutes. For many, this conjures seedy imagery of some low-life preying on society’s most vulnerable. In the words of our Justice Minister, I’m a pervert. Yet, despite the dark stereotype, I am a law abiding respectful person, loved and respected by my family, and very well regarded in my profession and by my community. Truth is, there is no such thing as a typical John or for that matter a typical prostitute. We all have a story to tell.”

“In my case I was married for close to forty years to my soul mate. Despite my loneliness, I refuse to replace my past love with another. It is unfair to ask a new partner to stand in as a life-long surrogate. I have found a solution that fits my needs: paid companionship. The women I meet come from all walks of life. These ladies are strong, intelligent and very well educated. They freely choose to be paid companions. They assume different roles: dinner companions, confidantes, sexual partners.”

I have to say, William doesn’t strike me as a misogynist or for that matter, a “pervert”. He doesn’t seem to have a shred of sadistic compulsion, and presumably. isn’t going after the underage girls, as so many do. And his rationale raises some interesting questions. What about escorts who don’t seem to be powerless, broken people; the ones who appear to be in that place by their own volition? What if, the interactions are less about sex and more about companionship? Is there a reasonable place to draw a line between exploitation and the legitimate purchase of companionship?

Those questions take me back to an interview* with Chelsea Haywood who, for three months, was a hostess in a Japanese men’s club. She captured her experience in a book, ’90 Day Geisha’. The bright young Canadian woman was 20 years old, socially engaging and well poised. Her job was to sit at a table with men and make conversation; perhaps not unlike William’s “dinner companions”. She was always impeccably (and fully) dressed and never sexually engaged the customers. In her words, “Your personality is your commodity.”

While it sounds like an easy gig, Haywood speaks of the “emotional demands” of the self-commodification and the exhaustion she, and her fellow hostesses, experienced. She suggests that those in this line of work should receive therapy and reports that many cope with excessive drinking and drug use. Likening her experience to prostitution, Haywood reveals “I wasn’t myself…I’d changed”.

Crediting her husband, at the time, for being “incredibly supportive,” Haywood says, “If he hadn’t been there, I think I would’ve fled after the third night.” But ultimately, the strain of the three months created “fractures” in her marriage, and she blames it on her divorce.

I could have chosen from countless stories much more tragic than Chelsea Haywood’s. But that’s the point. The personal cost of her short three months in paid companionship, free from a single violation of sexual boundaries, lends perspective when we hear of those who endure a more lengthy and intimate exposure.

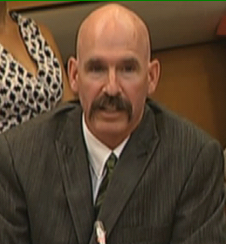

Because the sex trade follows law of supply and demand, one might also wonder about the effect of financing roles of paid companionship; especially when it includes “sexual partners”. Borrowing from my July 8th speech to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, men like William perpetuate “the processes of an industry that destroys young lives.” This is especially problematic in Canada because “a high demand for paid sex creates business opportunities for human traffickers.” I’m bold on these points because I’ve seen far too many young people who have been deeply wounded by the sex trade; most are trafficking victims, some are not.

Further to that, international studies continue to show that legal purchase of sex leads to a high demand for paid sex, which, in turn, leads to increased rates of human trafficking and a high incidence of prostituted minors. This phenomena is especially strong in western societies with strong economies, like Canada. While William may want no part in the harm caused be the sex trade, by virtue of his participation, I believe that he is in the wrong and he bears some measure of culpability in the violence.

MP Ève Péclet (NDP), one of the justice committee members, asked me if authorities were not further ahead to solely focus on the pimps, leaving the johns alone. The answer depends on the objective. If it’s to punish high pimps for harming people, that’s one thing. But understand, when you lock up a pimp, there’s always a “bubble gummer” ready to fill his shoes. If you want to see less young lives destroyed by the sex trade, you can’t win that fight unless you stem the demand. The way to do that is to criminalize sex buyers. (Incidentally, it was the NDP who invited, as a justice committee witness, sociologist, Chris Atchison. Mr. Atchison advocates for the rights of sex buyers and is the author of the project, ‘John’s Voice: Providing a Safe Place for Sex Buyers to Be Heard’.)

As William and I engaged in further dialogue, we did find some common ground. He pointed out the need to address the issues of unemployment, social benefits and lack of enforcement, noting these concerns are particularly important for women at risk and young girls. William also expressed a desire to see more support for outreach programs that provide viable alternatives to those women who are in ‘the life’ because of difficult circumstances. On that, he’s absolutely right.

William is right about another thing, we all have a story to tell; and I want to thank him for sharing his. When Bill C-36 becomes law, men like William could face criminal prosecution, at least where the purchase of ‘sexual services’ is concerned. Is that fair? You be the judge.

*90 Day Geisha, MacLean’s Magazine, December 2009